By Ray Schultz

Marketing guru Ron Jacobs has observed that “Consumers don’t have the patience anymore to read an eight-page direct mail letter.” True, and they probably don’t even have what it takes to read a four-page one.

But they must have had it in 1966, because that’s when Time magazine sent the following four-pager.

Like the classic Time letters from the 1940s and ‘50s, this one is a historical artifact. It introduces Ho Chi Minh, the leader of North Vietnam, to the American people. Then it goes on to quote Marshall McLuhan, mention both LBJ and Jimmy Hoffa in passing, and explain—in some detail—the benefits of Time.

The envelope features a line drawing of a pair of sandals, with this copy: “The wearer of these sandals said: “Americans don’t like long, inconclusive wars. This is going to be a long, inconclusive war.”

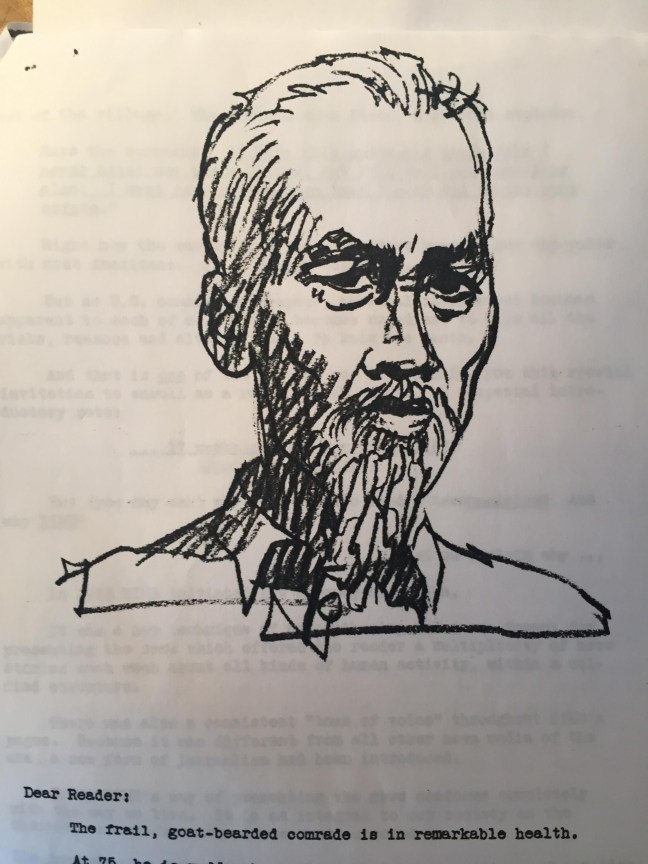

Inside, at the top of the letter, is a compelling image of Ho Chi Minh. Unfortunately, I have only a black-and-white Xerox copy, and did not write down the color of these illustrations. I suspect it was red.

Having found this letter in the Time Inc. archive, I am sad to report that it was one of the last of its type. That very year, Time started sending charmless, computer-generated sweepstakes letters, although Bill Jayme’s long Cool Friday letter was mailed into the 1970s.

There were no handwritten notes attached to this one, so I don’t know who wrote it, or how it pulled. And I wonder how many people, even those who snapped up the offer, made it all the way through. But here it is: One of the last great long letters written by Time’s direct mail masters. Enjoy.

Dear Reader:

The frail, goat-bearded comrade is in remarkable health.

At 76 he is ruddy-cheeked and cheerful. He dresses in –cream-colored, mandarin-style uniforms and “Ho Chi Minh scandals” carved from automobile tires. His tastes are exquisite. He smokes American cigarettes and dines on a rare delicacy called “swallow’s nest” – a marriage of sea algae and swallow’s saliva.

In 1962 Ho Chi Minh said: “We held off the French for eight years. We can hold off the Americans for at least that long. American’s don’t like long, inconclusive wars. This is going to be a long, inconclusive war.”

Drenched by a monsoon rain, a leathery U.S. Marine sergeant and his platoon wait in the swampy dark outside a wretched hamlet where V.C. are reported hiding. Finally a wan moon reappears. Its dim light glints on weapons carried by four fleeing figures heading out of the village. The marines open fire. A grenade explodes.

Says the sergeant: “I hate this goddamned place like I never hated any place before, but I’ll tell you something else: I want to win here more than I ever did in two wars before.”

Right now the war in Viet Nam is neither popular nor unpopular with most Americans. It is simply confusing.

But as U.S. commitment deepens, personal involvement becomes apparent to each of us. And it becomes expedient to know all the risks, reasons and alternatives. To know the facts.

And that is one of the reasons why I am sending you this special invitation to enroll as a regular TIME reader, at a special introductory rate:

. . . 17 weeks of TIME for only $1.87. (Just 11 cents an issue.)

But (you may ask) why do I want to read a newsmagazine? And why TIME?

Let me explain why…

In 1923 TIME initiated the newsmagazine idea.

It was a new technique of newsgathering and a new format for presenting the news which offered the reader a multiplicity of news stories each week about all kinds of human activity, within a unified structure.

There was also a consistent “tone of voice” throughout TIME’s pages. Because it was different from all other news media of the era, a new form of journalism had been introduced.

Today TIME’s way of presenting the news conforms completely with the way we live. It is as integral to our society as the electric and electronic wonders that surround us.

The newsmagazine form offers an integrated mosaic picture of our time…

Says Professor Marshall McLuhan, Canada’s social catalyst: “The newsmagazine form is pre-eminently mosaic in form presenting a corporate image of society in action…The reader of the newsmagazine becomes much involved in the making of meanings for this corporate image…”

After assembling what McLuhan calls “the crucial commodity of information” through many channels and from many sources, TIME prints only the most significant of that week’s news, news of greatest human interest. From all directions, covering all facets.

It is then up to the reader to assemble this mosaic of the news and discover for himself what it means…and by doing so becoming involved in his world in a way never before possible.

The reader begins to know who he is, what he is doing, and what it means to be a member of this particular society at this particular moment in history.

Thus the newsmagazine is recognized as a modern, efficient and essential tool of communication.

But how does this happen? How does the reader receive sufficient information each week to formulate his own meanings?

If you know TIME (and most people do) you know that it covers the news each week completely in23 separate sections. Among them: The Nation, The World, People, Education, Law, Religion, Medicine, Art, Modern Living, Music, Sport, Science, Show Business, Theater, U.S. Business, World Business Cinema, Books.

Each section of Time is also composed as a mosaic…

Take “Medicine” for example. In six consecutive issues TIME published the important news about infectious diseases, orthopedics, metabolic disorders , cardiology, physiology, parasitic diseases, gynecology, cancer, neurology, doctors, diagnosis, bacteriology, gastro-enterology.

In a single issues under “U.S. Business” there were stories on the economy, profits, auto, advertising, government, mining, banking. The following issue carried news of housing, publishing, publishing, communications, corporations, steel, money, retailing, oil, industry. And the next: shipping, airlines, finance, Wall Street, aviation, insurance, taxes.

One week recently under the heading “The Nation” TIME reported on President Johnson’s Hawaii Conference; the $3.39 billion foreign aid package; Senator Dirksen’s filibuster; Jimmy Hoffa; a wicked snowstorm; California’s Governor Pat Brown; Wyoming’s Governor Clifford Hansen; Mississippi’s Governor Paul Johnson; the Hudson River Valley; and the new head of all military construction in Viet Nam: Brig. Gen. Carroll Dunn.

TIME connects you with the world through a fascinating, complex, modern grapevine of information…

TIME’s staff of editors, writers, researchers and technicians scans the world to amass each week’s fund of new information. They read and translate millions of words, examine thousands of pictures, sift ideas, opinions, quotations, figures, reports….trimming, fitting, checking and transfixing it all into just about 125 columns of news and news-pictures each week. (TIME is a magazine for busy people.)

Each week too, there is an important Cover Story, a TIME Essay (on some subject as controversial as the Divorce Laws, or the Homosexual in America), and a color portfolio. With listings of what’s best in theater, movies, records, books, television.

Only an organization of TIME’s stature, structure and dimension could expend this amount of energy and effort.

But what is just as important: Time is a lot of fun to read … it often reads like fiction, humor or biography…

You can follow the exciting thriller 9reported from TIME’s Paris Bureau): “L’Affaire Ben Barka”, a sensational spy-murder-police scandal that has rocked France as the Dreyfus case did a the turn of the century.

You can play TIME’s new game of “barrendipity” (in contrast to “serendipity”, or the art of finding somewhere where you least expect to find it). Barrendipity is the art of not finding something where you might expect to find it: Danish pastry in Denmark, frankfurters in Frankfurt, English muffins in England, or baked Alaska in Alaska.

You can gain intimate knowledge of a great artist. From TIME’s Cover Story on pianist Arthur Rubenstein, who says:

“I’m passionately involved in life; I love its change, its color its movement. To be alive, to be able to speak, to see, to walk, to have houses, music, paintings – it’s all a miracle. I have adopted the technique of living life from miracle to miracle. Music is not a hobby, not even a passion with me. Music is me.”

With this weekly fund of news, insight, sidelight and background . . . you sense the unpredictable variety of life itself.

Writes Professor Marshall McLuhan: “By using our wits, we can translate the outer world into the fabric of our being.”

TIME helps you “translate.”

There is no set rule about how to read TIME. Some begin at the beginning. Others start from the back. What interests each man and woman is incalculable. So TIME tries to provide as much of interest and value to as many interested people as possible.

As the artists of 6th century Ravenna arranged mosaic tesserae according to size, contour and direction to create monumental designs, so TIME presents the design of our times.

Why not partake of this experience?

Our invitation is enclosed. It enrolls you at once as a TIME reader and brings TIME to your home or office regularly – for 17 weeks at only $1.87 (just 11 cents an issue).

Just put the card in the mail to me today – it’s already postage-paid.

And thank you.

Cordially,

Putney Westerfield

Circulation Director