By Ray Schultz

To the untutored, 1940 probably seemed like just another year ending in a zero. The movies Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz were playing around the country. On the radio, one heard Frank Sinatra singing with the Tommy Dorsey band. But some people were not consoled by such entertainment: The Germans were overrunning Europe, the Jews were in peril.

In March 1939, a charitable group called the Committee of Mercy, had sent a direct mail letter to people of good will:

Dear Friend:

The situation of the intellectual Jews who are still living in Germany in a state of misery, humiliation and ill-treatment attains a degree of horror which cannot easily be described in words. They endure it with great courage. They say:

“We do not mind so much for ourselves. We have made the sacrifice of our lives and of our welfare. We let them take our properties, our wealth, our factories, etc……We do not ask any help for ourselves, but for pity’s sake save our children.”

It was an eloquent plea, but the letter went on to offer anti-Semitic readers a way out: WILL YOU HELP? it asked. Or if you do not care to assist the Jews, will you aid the tubercular, and pre-tubercular children in France?

It’s not known how many recipients took either option. Either way, the letter reminded them, without explicitly saying it, that there could be another war.

Soon there was. And Time magazine hammered it home, both on its pages and in its direct mail pieces. This is America’s year, it said in a letter dated Jan. 2, 1940 and signed by Time’s circulation manager Perry Prentice. It continued:

All over Europe the lights are going out. All over Europe the nights are dark with fear.

But here in America the nights are bright with the lights of a thousand factories as America starts back to work after the long depression — bright with the lights of a thousand laboratories whose discoveries may change the course of history and all the ways of our living — bright with the lights of forty-million homes, where Americans are newly confident that they can find and conquer new frontiers in the American way.

Yes–this is America’s year — so this is the year you need TIME most.”

The letter went on to offer a subscription.

That was soon followed by:

Time has been banned in Germany!

Banned in Russia! Banned in Italy! Banned in Japan!

But here in America, where men are still free to think and learn the truth — thousands upon thousands of new families are turning to TIME each week to help them make the confusing news and war and peace make sense.

In February, at the height of the Phony War, Time sent a a direct mail piece, saying:

This is the dullest war in history…

FOR PEOPLE WHO DON’T KNOW WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT!

But it’s a tremendously exciting, moving, portentious war for those who know and understand what is really going on…

…tremendously exciting for the readers of TIME.

Two months later, with Hitler now on the march, recipients read this stark reminder:

When kingdoms vanish in the night…

– and nations wake to find the enemy within their gates..

Millions of people snap up each extra as it comes off the press and scan each headline in fear and horror – as puzzled children turn to parents for reassurance and explanation.

The real war had started. And in June, Time reported this

The Nazi Blitzkrieg has swept like a flame —

–over Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Northern France.

In eight short weeks kingdoms and governments have fallen, peoples have been subjugated, the balance of power of the whole world has changed.

It cannot go on much longer, many experts say — the next hundred days should tell the story.

In September, Time continued on its roll.

Dear American

Ours is the tragic previlege–

The tragic previlege of living and taking part in the greatest worldwide military crisis since Napoleon, the greatest American election crisis since Lincoln, the greatest economic crisis since Adam Smith.

And in times like these, when the news is so confusing and so dramatic and so immediately important — no American need be reminded that keeping thoughtfully well-informed is a personal duty.

Meanwhile, there was a struggle between isolationists like Charles A. Lindbergh, whose comments were tinged with anti-Semitism, and those who felt the U.S. had to help defeat Hitler. Among the latter was Henry Hoke, the 46 year-old Baltimore native and Wharton graduate who had befriended Louis Victor Eytinge. Hoke was ever on the alert for frauds who abused the medium, and he felt he had uncovered just such a group.

The Nazis.

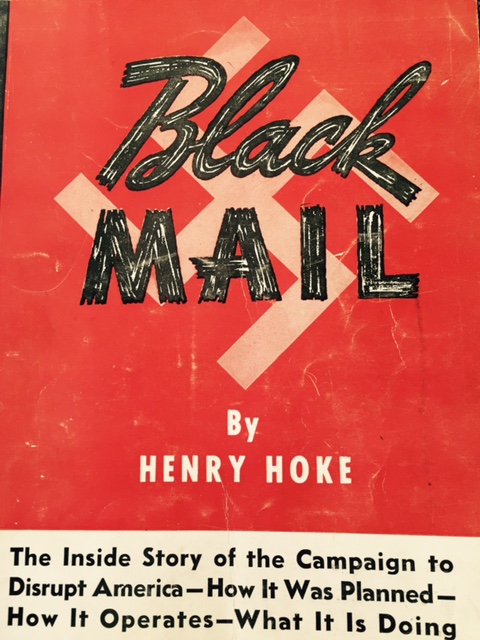

The Germans were using the U.S. mails to spread propaganda, and Hoke, whose son Pete had received pro-German circulars at Wharton, took it on himself to expose them. As he wrote later, in a book titled Black Mail, “the German government, through mail issued by specified agencies to selected lists, was attempting to divide the country so that the United States would be helplessly unprepared for future military attack.”

For instance, “the German Library of Information guided by Matthias F. Schmitz (assisted by George Sylvester Viereck), issued about 90,000 copies of a semi-weekly, well printed and written Facts in Review to ministers, school teachers, editors of college papers, legislators, publishers,” Hoke wrote in May 1940 in his magazine. “Purpose: to sell the National Socialist ideology and to prevent preparedness against attack.”

Then he added that “the German Railroads Information Office, guided by Ernest Schmitz, issued about 40,000 weekly mimeographed bulletins to hotel mangers, travel agencies, stock brokers, bankers and ‘small business men,’” to “convince Americans that the Nazi system of doing business was best.”

Hoke wasn’t done: “The American Fellowship Forum, guided by Friedrich E. Auhagen, assisted by George Sylvester Viereck, Lawrence Dennis, and others, issued pamphlets or bulletins to a ‘cultural class,’—educators, civic leaders, authors and a selected list of persons who might be sold the idea that the German mind was filled with nothing but the milk of human kindness for all humanity.”

It took courage to write that, even for an American tucked safely at home in Garden City, Long Island. E. Schmitz, from the German Railroads Information Office, wrote to demand that Hoke retract these “slanders,” and assured him that if he did, “a waiver will be given, releasing you and your publication from further claim.” Hoke noted that the letter “had been sent to my home…not to my office.”

Hoke published his exchange with Schmitz in a special mailing—“I refuse to be intimidated by you or by any German controlled organization. I refuse to have my family intimidated,” he wrote. And he got more outspoken as he realized the scope of the German operation.

“For the first time, it was possible to show how the Nazis had built a large mailing list (estimated at 250,000) of German Americans with relatives in Germany…how Japanese boats brought hulls full of printed material from Hamburg, Munich, Berlin…how these pieces were delivered under International Postal Union Treaties free of charge by the United States. (Under International Postal Treat, the country of origin retains the postage collected,” he wrote in Black Mail. “The country of delivery delivers free. A wash-out transaction to avoid bookkeeping).”

But the Germans were only part of it. Hoke found that Sen. Burton K. Wheeler, the Montana Democrat who had broken with Roosevelt over his court-packing plan, was sending out isolationist mail under his free Congressional frank. Analyzing the addressing on the envelopes, Hoke traced the pieces to a German group: the Steuben Society, Also sending seemingly pro-Hitler mail, for free, was Rep. Hamilton Fish (R-NY), who in 1938 had met with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in Europe, and reportedly said that Germany’s demands in Poland were “just,” according to Hoke.

Hoke deplored the anti-Semitism shown by many isolationists. “On April 25, 1941, in Omaha, Nebraska, Charles B Hudson, violently anti-Semitic publisher, admitted to reporters that he had distributed isolationist speeches under the Congress free mailing franks of Senators Worth Clark of Idaho, Bennett Champ Clark of Missouri and Burton K. Wheeler of Montana, and Representatives Oliver of Maine and Bolton of Ohio,” he reported.

Hoke wrote to Wheeler: “Unaddressed franked mail under your signature and under that of former Representative Jacob Thorkelson of Montana, has been distributed by your violent adherent Donald Shea at his anti-Semitic meetings and by Nazi-loving, Jew-baiting Joe McWilliams at Christian Front meetings. Recipients were instructed to address the franked envelopes and dump them into the nearest postal box, without payment of postage.”

Of course, isolationists had a right to circulate their views, although not under franked mail, Hoke argued. Wheeler fought back. “I am not seriously concerned about Mr. Hoke’s misrepresentations,” he wrote in a letter. “In the first place, Mr. Hoke is interested in direct mail advertising, as he himself says, and is opposed to the use of the franking privilege on general principles.”

Wheeler then claimed that “Mr. Hoke makes no reference to the fact that those in Government who apparently favor our intervention in foreign war sent out under various Congressional franks some 2,00,000 pieces of mail all over the United States, much of it distributed by the pro-interventionist committees and organizations.”

Wheeler also falsely wrote that Hoke was employed by the Anti-Defamation League of the B’nai Brith, as if that discredited him. Meanwhile, Hoke reported that the supposedly good name of the Order of the Purple Heart was being used as a cover in the scheme.

Events moved quickly. FDR was elected to an unprecedented third term in November 1940. On June 2, 1941, Hoke wrote, “a friend beside a news ticker called me on the ‘phone to beat the headlines…’Henry, you ought to be glad to know,’ he said, ‘the President of the United States has just issued an executive order closing the German Railroads…the German Library of Information…and the German Consulates.’”

Hoke was pleased, although this crusade had practically wrecked his business. But he kept after the Nazi sympathizers, using the techniques of his trade to undo them. For example, friends wrote flattering letters to the appeasers, using dummy names, and soon received isolationist letters addressed to those names, fueling his investigative reporting. And more was to follow.

“We learned from a girl who worked in a locked and guarded room on the top floor of the Ford Building at N. 1710 Broadway in New York City that Ford Motor Car Company employees were compiling a master list of appeasers, anti-Semites, pro-Nazis and Fascists from fan mail addressed to Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh, to former Senator Rush Holt and to Representative Hamilton Fish,” Hoke wrote.

He added that “the lists, when compiled, were delivered to Bessie Feagin, circulation manager of Scribner’s Commentator. That explained how some of the dummy names used in writing to radio orators eventually got on the list of the American First Committee and Scribner’s Commentator. But why the Ford organization? But why…a lot of things?”

Feagin was eventually hauled before a grand jury, as were many others, including Hamilton Fish. “No one knows what Hamilton Fish told the Grand Jury on December 5, 1941,” Hoke said. “Someone was pulling every possible string to have the case buried.”

Two days passed. Then: “Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941, just as our little family sat down to dinner…the flash we feared came over the radio…Pearl Harbor!”

Time wasted no time in getting letters out:

Dear American:

And now the news is happening to us!

Its unpredictable turns and changes are altering the whole course of your life — the job you work at, the town you live in, the clothes you wear and the food you eat.

The news is happening to you in the Pacific — and sudden developments in Malaya and the China Sea, at Singapore and off San Francisco, in Tokyo and Manila and the Dutch East Indies can change your life more than you can possibly change it yourself.

The news is happening to you across the Atlantic — where Russia bleeds Germany white, where American tanks fight the Axis in Libya, where Britain waits tense for an attempted invasion – and your life and my life, the safety of our families and the future of our children all wait on tomorrow’s news.

The news is happening to you at home — where new laws and new regulations pour out of Washington – where entire industries are changing over to war production, where uniforms fill the streets and the whole nation moves with a new unity and determination.

Yes, the news is the biggest things in our lives today – stirring and vital and very near us all. And it is very confusing.

And that is why this is the year you need TIME most.

Despite this development, and the collapse of the America First organization, the flow of isolationist mail continued, some letters containing vicious attacks on “the Jews.” George Sylvester Vierick was indicted by the Federal Grand Jury for failure to give a true statement of his activities in registering as a german agent, and held on $15,000 bail. (Nazi agent).

Hoke recorded the scene:

“11:30 P.M. Judge Lawes appears and the courtroom is filled with an air of dignity…and tension. The jury walks in a semi-circle at the side of the bench. Viereck stands before the jury and glares. The clerk reads each count and the foreman answers—‘Guilty’…six times. Vierecks lawyer asks that the jury be polled. Viereck glares at each juror as the question is put six times, an the answer six times is ‘Guilty.’ Seventy-to times Viereck hears his ‘fellow citizens’ say the word ‘Guilty.’ The big marshal standing behind George Sylvester Viereck takes out his handcuffs and the Nazi agent goes out through the back door. Court adjourned.”

It was the last blast for Viereck—and also for junk mail. As they had in World War names disappeared from iists—these men were unreachable. Not that it mattered– there were paper shortages that prevented mail pieces from being printed. And there was nobody to send them, for copywriters and list brokers were now in uniform. Except for the mail sent by charitable fundraisers, like the people who served coffee and donuts to servicemen, the business was on hold.

Chapter 27: The Veteran’s List