By Ray Schultz

Suffering from cancer or leukemia? Had a stroke or two? Don’t despair, friend. You can reverse these illnesses with a common syrup: a miracle cure that can also help you rebound from heart attacks, diabetes and everything else right down to post-nasal drip.

So said a classic direct mail piece that promoted a “nine-day inner cleansing and blood wash.” It was sent some years ago by the brilliant copywriter Eugene Schwartz.

How could he get away with this baloney without bringing the Federal Trade Commission down on his head?

It’s simple. Gene never offered the actual products: Rather, he peddled a book that told about them. And under the so-called Mirror Image rule, you can’t get in trouble for selling a book as long as your marketing copy accurately describes what’s in the volume.

Granted, he didn’t mention the book until the second-to-last paragraph in the four-page letter signed by one I.E. Gaumont. And he qualified the offering with this notice on the bottom of the very first page:

“The statements contained in this book express the opinions of the author, who is not a medical doctor.” Who knows if he was forced into including that?

Gene Schwartz has been dead for over 20 years, but there is much to learn from his copywriting approach: it wasn’t wordsmithing, but vision, to steal a phrase from the late Andi Emerson.

Mind you, Gene believed in naturalistic healing, claiming that it helped him recover from his own stroke in 1978. And his “authors” were real people, who believed in the cures they were hyping.

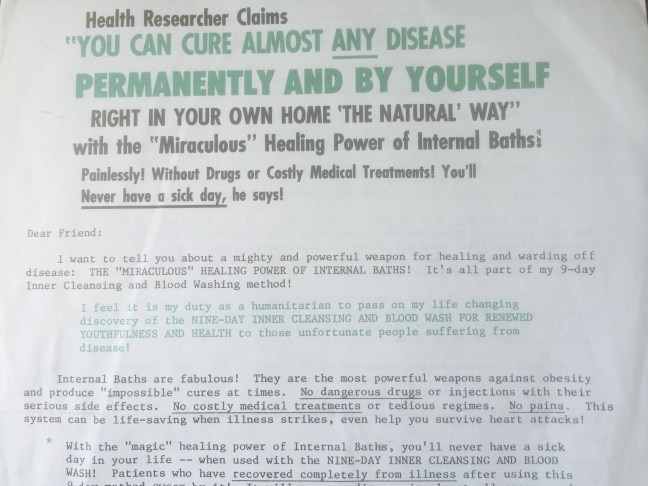

Who was Gene Schwartz? The six-foot-four legend from Montana was known as much for his art collection and service on museum boards as he was for his direct mail copy. (Click here for his bio). But he was one of the greatest copywriters who ever lived. And here he is at his best. (There’s a bad visual of the letter at the bottom).

Health Researcher Claims

“YOU CAN CURE ALMOST ANY DISEASE PERMANENTLY AND BY YOURSELF

RIGHT IN YOUR OWN HOME ‘THE NATURAL WAY’ WAY” with the “Miraculous” healing Power of internal Baths:

Painlessly! Without Drugs or Costly, Medical Treatments! You’ll Never have a sick day, he says!

Dear Friend:

I want to tell you about a mighty and powerful weapon for healing and warding off disease: THE “MIRACULOUS” HEALING POWER OF internal BATHS! It’s all part of my 9-day Inner Cleansing and Blood Washing method!

I feel it is my duty as a humanitarian to pass on my life changing discovery of the NINE-DAY INNER CLEANSING AND BLOOD WASH FOR RENEWED YOUTHFULNESS AND HEALTH TO those unfortunate people suffering from disease!

Internal Baths are fabulous! They are the most powerful weapons against obesity and produce “impossible” cures at times. No dangerous drugs or injections with their serious side effects. No costly medical treatments or tedious regimes No pains. This system can be life-saving when illness strikes, even help you survive heart attacks!

*With the “magic” healing power of Internal Baths, you’ll never have a sick day in your life – when used with the NINE-Day CLEANSING AND Blood WASH! Patients who have recovered completely from illness after using this 9-day method swear by it! It will conquer disease in almost all cases, and free your body of accumulated poisons that make you sick, in only 9 days!

Here’s what happens during the 9 days of cleansing:

*It will rid your body of poisonous wastes (toxins) that have accumulated and formed a lining around your intestinal wall – causing disease

*It will reverse the aging process, and increase your longevity by 20 years!

*It will reduce your weight without dieting or the use of drugs – and keep you slim during your lifetime!

*It is a positive way to avoid ever having a heart attack. It may keep you alive even if you’ve had a heart attack or stroke!

*It will heal arthritis if not in the advanced stages!

*It will lessen the intake of insulin by diabetics!

*It will restore masculine vigor and put energy back in your sex life!

*It will overcome low blood sugar!

*It will aid in normalizing high blood sugar!

*It will overcome post nasal drip!

*It will overcome an urge to urinate too frequently

…and still that’s just the beginning!

SECRET DISCOVERY REVEALED!

At this writing, I am 84 years young. When I first began my investigations, I was in a state of broken health. I suffered from bronchitis, shortness of breath, sinusitis, gastritis, acidosis, high blood pressure, constipation, chronic fatigue, backache, obesity, and hay fever. Then, about 35 years ago I discovered the NINE-DAY CLEANSING AND BLOOD WASH!

Today, at 84, I am a well preserved individual, hale and hearty, mind sharp as a razor and productive. I am erect in stature, with a youthful 34-inch waist, a full crop of silver-white hair an no wrinkles on my face.

My wife, Connie, at the young age of 70 “going on 50,” hasn’t been to a medical doctor in about 20 years. I did not have occasion to see a doctor until I was 65 when I thought it best to start having check-ups. I’ve only had one brief illness in 3 years.

What is the secret!

Inner cleansing! You see, my studies revealed to me that many illnesses seem connected with cell stagnation. If your nose is “stuffed up” or congested, or if you experience congestion in your throat or chest, it indicates that there is an accumulation of stagnant matter within you…sinus trouble, bronchitis, asthma, or colitis, is the result of stagnation. So are arthritis and skin eruptions.

All this can be prevented by giving the body an opportunity to cleanse and purify itself, and then rebuilding the body and its cells with proper nourishment.

FOUR NATURAL BLOOD WASHING FOODS WITH HEALING POWER!

During the 9 “Cleansing Days,” you’ll be eating certain foods I recommend. During this time, you will also begin the action which will effect a good, thorough wash of your bloodstream. You’ll simply begin to sip certain fresh juices.

What are these foods? There are several, but during my years of research. I have singled out FOUR NATURAL BLOOD-WASHING FOODS WITH HEALING POWER that play an important part in healing, curing, and preventing disease.

You may be skeptical, but remember, the NINE-DAY Inner Cleansing and Blood Wash which I take yearly, has warded off common ailments and most pernicious diseases. It has kept me in the best of health throughout the years..and I am 84. If I merely told you the names of these foods you might not be impressed. But wait till you see what doctors, nutritionists, scientists, researchers, an users themselves say!

BLOOD WASHING FOOD #1: NATURE’S CURATIVE WONDER FOOD!

One of these foods, a common syrup, is in my opinion, an Unheralded Cancer Fighter. I believe it will not only close the door on cancer in general, but is especially helpful in cases of leukemia, strokes, ulcers, arthritis, varicose veins, and menopause

*James P. was in a state of broken health, unable to do even the lightest work. He was suffering from a growth in the bowels, blocked bronchial tubes, constipation, indigestion, pyorrhea, sinus trouble, and weak nerves. In addition, he was losing weight, and his hair and turned white – despite medical treatment. On hearing of a remarkable cure with this syrup, he decided to try it himself. And not only did the growth in his bowels disappear, together with all the other troubles, but his hair actually regained its original color (he was over 60 at the time).

Others, apparently, have had the same remarkable results, including a man with a fibroid growth of the tongue, and another with cancer of the knee. Reputedly, tumors in various parts of the body have withered away without any other measures than taking this syrup. (No cancer cure is claimed, and reputable medical help is advised, of course, in all cases.)

*A “MIRACLE RECOVERY” FROM TWO STROKES! It is widely thought that when a person has had two strokes the third will be fatal – and yet it need not be so. Mr. K., an elderly man, had had two strokes and was completely paralyzed on one side. He then tried this syrup. The result was that he recovered the use of all his limbs and became completely fit, much to the astonishment of his doctor.

*SPECTACULAR CURES OF ARTHRITIS! Elaine B., 60, had severe arthritis in her knees and hip joints. She was in a great deal of pain and was unable to walk without assistance. Finally, she tried this syrup. One week later, she could swing her legs and flex her knees painlessly! Mr. J., an elderly man, could barely hobble with canes. After using this syrup for four weeks, he threw away his canes!

This common syrup can be obtained at any health food store or supermarket at negligible cost. There is nothing like it for prevention of these diseases I always take my quota of this syrup every day. I strongly recommend that you do the same. It’s a must! Several men who had been denied driver’s licenses because of heart trouble were put on treatment with this syrup. After six weeks they got their licenses. A woman afflicted with recurrent heart attacks took this syrup and the attacks subsided!

BLOOD WASHING FOOD #2: A WONDER BEVERAGE!

It has been said that there are a number of ailments that will automatically disappear after taking this beverage in a certain manner. It is made of the most health-giving fruit that exists.

It has been said that there are a number of ailments that will automatically disappear after taking this beverage in a certain manner. It is made of the most health-giving fruit that exists.

Reduction of weight without dieting will be achieved permanently if this beverage is taken a few times a day. It will burn up the surplus fat. It retards the onset of old age…renders the urine normal thus counteracting a too-frequent urge to urinate)…it promotes digestion because it is very much like a digestive juice!

Observers have been quite astonished to see how forgetfulness in old people partially or wholly disappears through the practice of taking this beverage. Excessive bleeding can be reduced to a minimum in the case of an operation, and the healing process greatly quickened, if the patient takes this beverage. In cases of frequent nose-bleeding due to some unknown cause, a drink of this beverage with each meal will soon put a stop to the trouble. Sore throats – even of the streptococcus type – can be cured with astonishing rapidity, often in one day, by taking this beverage as a gargle. Tickling coughs and laryngitis will rapidly disappear. It regulates menstruation and is very beneficial to women. Belching can be cured or greatly lessened by taking this beverage.

BLOOD WASHING FOOD #3: A FOOD FOR HEALING!

Here is another syrup that is a most effective remedy for insomnia, emphysema, shortness of breath, sinusitis, asthma, and chronic fatigue. Combined with a certain beverage I tell you about it, it is most beneficial to those suffering from various heart troubles, hay fever, colitis, arthritis, neuritis, and many other common ailments. It is a natural laxative, and one of nature’s most powerful germ killers.

Russian medico-scientists have shown that it will cure a condition as serious as gastric ulcers. One doctor wrote: “In heart weakness I have (this syrup) to have a marked effect in reviving heart action and keeping the patients alive.”

BLOOD WASHING FOOD #4: A 3,000-YEAR-OLD MIRACLE MEDICINE!

This vegetable is the oldest known “home remedy.” It has long been used to rid the body of parasites and in the healing of disease. According to an old news item, “in test tube experiments Virile bacilli that can be killed only after hours of boiling in water die, after one hour of exposure to (this vegetable).”

This vegetable’s almost miraculous antiseptic power is an aid of high blood pressure, asthma, emphysema, colds, gas, gall stones, bronchitis, infections, hardening of the arteries, mucus, elimination, sinus trouble, and many other maladies. It has been widely used in restoring masculine vigor. It clears the blood of excess sugar as effectively as an oral drug. It has remarkable preventive powers and healing powers and offers protection against heart disease.

POWERFUL WEAPONS YOU CAN USE TO OVERCOME MAJOR DISEASES!

The diligent use of these 4 foods, with their extensive curative properties, healing powers, and remarkable preventive powers, will aid tremendously in “healing the body” in my opinion. They are all part of my NINE-DAY INNER CLEANSING AND BLOOD WASH FOR RENEWED YOUTHFULNESS AND HEALTH!

SEND TODAY FOR FREE TRIAL COPY!

Mail the enclosed card for your FREE trial copy. You have 15 days to discover all the incredible health-building secrets that will bring amazing youthfulness to your body: honor the invoice for four easy payments $6.98 pus applicable state tax, postage handling – or return the book and owe nothing.

Sincerely yours

I.E. Gaumont

REWARD BOOKS

Health & Self Improvement

IMPORTANT NOTICE [appearing at bottom of first page of letter):

The statements contained in this book express the opinions of the author, who is not a medical doctor. These opinions may, in certain cases, be contrary to those of the medial professions, and are based on experiences which may not be representative of results that can be expected for others. The publisher suggests that you do not attempt to make a self-diagnosis based on the symptoms referred to. Many of those symptoms can be caused be more than one condition, and these conditions cannot be self-diagnosed by the lay person. Where cancer may be involved, early diagnosis and treatment may be critical. In all cases, early diagnosis and treatment by a competent medical practitioner is advisable and, in some case, may be essential.