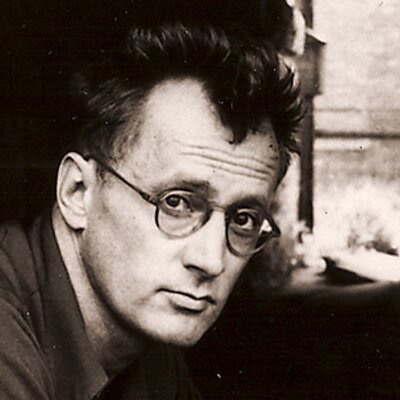

Book Review: Never A Lovely So Real—The Live and Work of Nelson Algren by Colin Asher, W.W. Norton & Company 2019

By Ray Schultz

Nelson Algren was seen by some as the bard of the dispossessed and by others as the bard of the stumblebum. The operative word was bard. Algren was a poet who wrote novels, not a novelist who wrote poetry, one critic–I believe it was Seymour Krim–observed. And he penned several American classics, the very titles of which have entered our language, like A Walk On The Wild Side.

Algren died in 1981 at age 72. Since then, there have been three pretty good biographies of him. The latest, Never A Lovely So Real, by Colin Asher, has been hailed as the definitive treatment. But will it supplant Bettina Drew’s 1989 effort: Nelson Algren—A Life On The Wild Side? And do any of them recognize the poetry and depth in Algren’s writing and view him as much akin to Faulkner as to Dreiser?

Asher gives Algren his due in a robust book providing new visibility into Algren’s life and work. And he lets us in on at least a few things that were not widely known. One is the fact that Algren, a “gut radical,” as I heard a friend describe him, was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953, and that the FBI’s surveillance of him and the cancellation of his passport hurt his morale and ability to write more than many people realized. Some friends may have thought that Algren was having a breakdown over gambling losses and his marital woes when he seemed to attempt suicide, falling into a frozen lake in Gary, Indiana.

The basic biographical details are, of course, known to Algren fans. The former Nelson Algren Abraham, who grew up on the South Side of Chicago and bummed around the country in boxcars during the Depression, wrote one novel that didn’t attract much notice, Somebody In Boots, then broke through in 1942 with Never Come Morning.

Never Come Morning, tells the story of Bruno Lefty Bicek, a would-be boxer who allows the entire membership of the Baldheads Athletic Club to gang-rape his girlfriend Steffi in an alley under the El. Bruno kills a Greek youth who wants to join in, saying the fun Is “for whites only,” and in the end must pay for this crime–“I knew I’d never get to be 21 anyway,” he says. In telling this grim tale, Algren moved beyond the leftist clichés of the era and replaced them with prose so moody and powerful that the Nation identified Never Come Morning as the work of a depressed man. Ernest Hemingway admired the novel, and wrote, “You should not read it if you cannot take a punch.” Never Come Morning went on to sell a million copies in paperback.

Algren served as an Army medic in Europe in World War II, but never did the war novel people expected. Instead, living in a $10-a-month flat at Wabansia and Bosworth in Chicago, he wrote a post-war novel–about a card dealer who comes home with a Purple Heart and a morphine habit: The Man With the Golden Arm. It is a vast artistic advance over his prior work, filed with pre-Beat argot, bedroom farce and stunning interior monologue.

The poetry and humor are present in the first two paragraphs, which Asher quotes in full:

The captain never drank. Yet, toward nightall in that smoke-colore season between Inian summer and December’s first true snow, he would sometimes feel half drunken. He would hang his coat neatly over the back of his chair in the leaden station-house twilight, say he was beat from lack of sleep an lay his head across his arms upon the query-room desk.

Yet it wasn’t work that wearied him so and his sleep was harrassed by more than a smoke-colored rain. The city had filled him with the guilt of others; he was numbed by his charge sheet’s accuations. For twenty years, upon the same scarred desk, he had been recording larcency and arson, sodomy and simony, boosting, hijacking and shootings in sudden affray; blckmail and terrorism, incest and pauperism, embezzlement and horse theft, tampering and procuring, abduction and quackery, adultery and mackery. Till the finger of guilt, pointing so sternly for so long across the query-room blotter, had grown bored with it all at last and turned, capriciouly, to touc the ribers of the dark gray muscle behind the captan’s light gray eyes. So that though by daylight he remained the pursuer there had come nights, this windless first week of December, when he had dreamed he was being pursued.

Quite an opening. Unfortunately, writers who quote this always leave out the paragraphs that follow:

Long ago some station-house stray had nicknamed him Record Head, to honor the retentiveness of his memory for forgotten misdemenors. Now drawing close to the pension years, he was referred to as Captain Bednar only officially.

The pair of strays standing before him had already been filed, beside their prints, in both his records and his head.

“Ain’t nothing on my record but drunk ‘n fightin’,” the smshednosed vet with the bufalo-colores eyes was reminding the captain. “All I do is deal, drink ‘n fight.”

The captain studied the faded suntans above the army brogans. “What kind of discharge you get, Dealer?”

“The right kind. And the Purple Heart.”

“Who do you fight with?”

“My wife, that’s all.”

“Hell, that’s no crime.”

He turned from the wayward veteran to the wayward 4F, the tortoise-shell glsses separating the outthrust ears: “I ain’t seen you since the night you played cowboy at old man Gold’s, misfit. How come you can’t get along with Sargeant Kvorka? Don’t you like him?”

These paragraphs establish the friendship between the card dealer Frankie Machine and his half-Jewish mascot Sparrow Saltskin, known as the punk, and the continuing presence of the police in both their lives.

The novel was said to be the first to depict drug addiction, and the first to use the phrase that an addict has a monkey on his back. But the real strength of this tragedy is in is the cast of characters—Blind Pig (or Piggy-O), Molly (or Molly-O), Drunkie John, Antek the Owner and Nifty Louie the drug dealer. “Algren makes his living grotesques so terribly human that their faces, voices, shames, follies, and deaths can linger in your mind with a strange midnight dignity,” Carl Sandburg wrote.

Thanks, in part, to these virtues, The Man with the Golden Arm was a bestseller, and it won for Algren the first National Book Award. But what would he do next? The successful author went on to pen Chicago City on the Make, a prose poem that focused on the underside of the city.

It isn’t hard to love a town for it greeter and its lesser towers, its pleasant parks or it flashing ballet. Or for its broad and bending boulevards, where the continuous headlights follow one another, all night, all night and all night. But you never truly love it till you can love its alleys too. Where the bright and morning faces of old familiar friends now wear the anxious midnight eyes of strangers a long way from home.

A midnight bounded by the bright carnival of the boulevards and the dark girders of the El.

Where once the marshland came to flower.

Were once the deer came to water.

The slim volume, which is now considered a classic, also featured the line, Every day is D-Day under the El.

Next, Algren wrote a book-length essay on being a writer in a time of the hydrogen bomb, originally to be titled A Walk On The Wild Side.. It showed that Algren saw himself as “a multifaceted writer of the old school—and axiomatically a social critic—rather than simply novelist,” Bettina Drew writes. But Doubleday, unwilling to be labeled a “Red” publishing house, refused to publish it. And the manuscript was lost for 40 years.

Meanwhile, Algren had started a novel called Entrapment, based on the story of his onetime lover Margo (identified by Asher as one Paula Bays, in what he apparently considers a scoop), a woman who kicks a heroin habit. He was prepared to spend years on it, working from the inside out, building it in layers. Then he made a wrong turn: To earn an advance, he started revising his first novel Somebody In Boots under contract to Doubleday, and it evolved into the semi-comic work we know as A Walk On The Wild Side, a book that reportedly has influenced everyone from Lou Reed to Dan Dellllo. But it was the wrong book: Algren should have been working on Entrapment.

Not that A Walk On The Wild Side lacks Algrenesque virtues or poetry, some of held over from Somebody in Boots. Algren had learned valuable lessons when riding around in boxcars–like how to avoid the dreaded railroad bulls.

Look out for Marsh City—that’s Hank Pugh’s. Look out for Greeneville—that belnogs to Buck Bryan. Buck’ll be walking the pines dressed like a ‘bo—the only way you’ll be able to spot him is by his big floppy hat with three holes in the top. And the hose length in his hand.

Your best bet is to freeze and wait. You can’t get away. He likes the hose length n his hand but what he really loves n the Colt on his hip. So just cover up your eyes and liten to the swwisshhh. He’s got deputies coming down both sides. God help you if you run and God help you if you fight. God help if you’re broke and God help you if you’re black.

Look out for Lima—that’s in Ohio. And look out for Springfield, the one in Missouri. Look out for Denver and Denver Jack Duncan. Look out for Tulsa. Look out for Tucson. Look out for Joplin. Look out for Chicago. Look out for Ft. Wayne—look out for St. Paul—look out for St. Joe—look out—look out—look out-

Doubleday declined to publish A Walk On the Wild Side, seeing it as too salacious. Algren found another publisher, but while the novel sold well and was later made into a movie, it was ferociously reviewed and Algren was headed for a personal and professional collapse. He stopped writing novels and morphed into the slightly clownish figure we later knew, who wrote travel books, lampooned other writers, lost money at the track and had his dentures broken while living for a time in Saigon.

Factual Errors

Asher recounts all of this with sympathy. But I have several issues with his reporting, some petty, some not.

For one, in describing Algren’s first meeting with the French author and feminist Simone de Bouvoir in 1947 (an acquaintance that instantly blossomed into a romance), Asher writes that Algren “boarded the El on a Friday evening and rode it toward the Loop—beneath Milwaukee Avenue, through the narrow tunnel under the Chicago River, and then south under State Street.”

Actually, the subway under Milwaukee Avenue didn’t open until 1951, and it runs under Dearborn Street in the Loop, not State Street. In 1947, Algren would have had to take the El (or “L,” as the system is branded) the long way around from his neighborhood.

Asher also writes that when living in Sag Harbor, Long Island at the end of his life, Algren “he slipped into the frigid Atlantic and swam a little, but not a lot.” Sag Harbor is located on a bay, not the ocean. And the writer Pete Hamill’s name is misspelled in the citations. The errors add up, and at some point it reads like a badly sourced Wikipedia entry.

Worse, Asher reports that St. Louis was seething when Algren arrived with some tough-guy friends in the autumn of 1955. “A six year-old boy named Bobby Greenlease had been kidnapped and murdered the month before by a man with mafia connections, and three people had been killed since.”

That is wildly inaccurate. Bobby Greenlease was kidnapped and murdered by a pair of losers named Carl Austin Hall and Bonnie Heady in September 1953. Both were put to death in the Missouri state gas chamber exactly two months after this crime.

Entrapment

Then there are a couple of serious omissions about Algren’s career. One is any real account of Entrapment, the novel Algren abandoned after his personal breakdown. Asher mostly mentions this unfinished novel in passing, referring to it as “picaresque.”

Picaresque?

Going by the fragments published in the 2009 book “Entrapment And Other Stories,” I suspect that the novel was gong to start like this: “Now remember this if you can,’ the ancient one-eyed jackal warned Real High Daddy, `you can always treat a woman too good. But you can never treat her too bad.”

From there, Entrapment would have moved into sections written in different voices, a technique Algren used to telling effect in the short story, The Lightless Room, about a boxer killed in the ring, and as Faulkner had done in As I Lay Dying. For example, there is Baby’s recollection of how Daddy got her onto “junk:”

I was still that simple I didn’t know what he meant.

I found out in due course. In that same room right under the roof where you had to battle for every breath.

On that day so still so burning.

That last line is especially effective the second time it is used.

In his own meditations after the woman has left him, the male character thinks that Here in his own patch between billboard and trolley everyone tried, their whole lives long, to be somebody they never were. Somebody they’d read about, somebody they’d heard about, somebody they never could be. Somebody like George Raft, somebody like Frank Costello, someone like Myrna Loy. It was a world full of big shots, fake shots that fooled nobody except the big shots themselves.

Drew devoted an entire chapter of her book to Entrapment, saying that based on the portions available “this would have been a significant work.” Editor William Targ agreed that Algren “seemed to reach the deep-down essence of the blackest lower depths: drugs, pimping, prostitution, at their most grim level…It would have been an extraordinary achievement…it could have been his magnum opus.”

Yet the National Book award winner and bestselling author couldn’t get a contract for it, although one large portion was published in Playboy.

It’s our loss. Drew writes that “Entrapment, conceived in the spirit of Never Come Morning and The Man with the Golden Arm, would never be finished, and the naturalistic writer in the tradition of Wright and Sandburg and Dreiser was gone.”

I’ve always thought that Algren is trivialized by people who insist on quoting his line: Never eat a place called Mom’s, never play cards with a man called Doc and never sleep with someone whose troubles are worse than your own. Algren was a serious artist who deserves to be remembered for more than that.

Asher seems to agree. But then Asher does something similar, using perhaps the worst line in Chicago City on the Make, likening Chicago to a woman with a broken nose, for the title of his own book.

That’s not his only misstep. Asher also writes that Algren was not great at titles.

Huh? He says that about the man who has given us such titles The Man With the Golden Arm, The Neon Wilderness, A Walk On The Wild Side, The Devil’s Stocking, Chicago: City On The Make and Native Son (the title he wanted for his first novel until someone stupidly changed it)? Algren’s sometime friend Richard Wright used Native Son, although it’s not clear who got it from whom.

Algren’s Posthumous Career

Finally, there’s Algren’s posthumous career. Algren published only nine proper books during his lifetime, and he edited one collection. After he died, Algren fans were treated to this quartet of significant works:

1983—The Devil’s Stocking

1994—The Texas Stories

1996 – Nonconformity (the essay formerly known as A Walk on The Wild Side).

2009— Entrapment and Other Stories

The Devil’s Stocking, Algren’s first novel in 25 years, was based on the murder case of boxer Ruben Hurricane Carter, with several characters and situations added, including vivid accounts of the houses of ill repute around Times Square.

Asher states that Algren’s prose had flattened out, and that the poetry was gone. I disagree. While it may not rival The Man With The Golden Arm, the Devil’s Stocking has its own rhythm and poetry. Take its description of the future prostitute Dovey Jean Dawkins:

Once a teacher, calling her by her first name with an accent of sympathy, wakened in the child a feeling of great love. For she had great love in her.

Nobody needed it. Nobody wanted it. Love was a drag on the market.

Then there is the fighter’s father, who once brought his son to the police after he caught him in a theft.

“I never knew the police would take such hold,” he admits.

“You know it now, old man,” a friend says.

never knew the police would take such hold,” he admits.

The man still had it, and Asher does correctly note that The Devil’s Stocking was Algren’s best book in years.

If only Algren had completed Entrapment and the proposed short story collection, Love In An Iron Rain. But as Studs Terkel said in a brief conversation I had with him in 1982, Algren did what he did. He made his statement.

So has Bettina Drew. Her biography is still the one to beat.